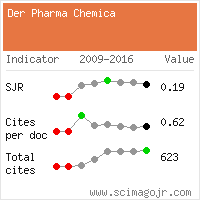

Review Article - Der Pharma Chemica ( 2022) Volume 14, Issue 8

An Updated Review on Catharanthus Roseus: Its Traditional and Modern Use for Humankind

Nikki Sadaphal1* and Dr. Chitra Gupta22Department of Chemistry,Bundelkhand University Campus Jhansi (U. P.), India

Nikki Sadaphal, Department of Chemistry, Govt. Thakur Ranmat Singh College Rewa (M.P.), India, Email: nikkibangar.lucky@gmail.com

Received: 24-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. dpc-22-67568; Editor assigned: 28-Jun-2022, Pre QC No. dpc-22-67568; Reviewed: 16-Jul-2022, QC No. dpc-22-67568; Revised: 25-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. dpc-22-67568; Published: 01-Aug-2022, DOI: 10.4172/0975-413X.14.8.48-54

Abstract

Medicinal plants are a blessing to humans since they are being used to treat existing and emerging ailments, either directly or indirectly. However, the availability of such plants, as well as their characteristics, has an essential impact. Catharanthus roseus is a very important medicinal herb in this direction as availability and its property both are fortunate thing for humankind. It is an evergreen plant first originated from islands of Madagascar. The flowers may vary in color from pink to purple and leaves are arranged in opposite pairs. It produces nearly 130 alkaloids mainly ajmalcine, vinceine, resperine, vincristine, vinblastine and raubasin. It is known for its antitumor, anti-diabetic, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant and anti-mutagenic effects. It has high medicinal values which need to be explored extensively. The purpose of the current study is to document updated data about its traditional and modern uses.

Keywords

Catharanthus roseus; Alkaloids; Medicinal use

INTRODUCTION

Plants are an essential part of human society since the civilization started. Medicinal plants are the boon of nature to cure a number of ailments of human beings [1]. These plants have a long history of usage in traditional medicine [2]. The dependence of human beings on plants dates back to the start of the human race. Medicinal plants are common sources of medicine. Solid evidences can be cited in favor of herbs being used for the treatment of diseases and for restoring and fortifying body systems in ancient systems of medicine such as Ayurvedic, Unani, and Chinese traditional medicine. The authentic knowledge of the usage of medicinal plants passed from one generation to another, after refining and addition [3]. The folk recipes are prepared either from the whole plant or from their different organs, like leaf, stem, bark, root, flower, seed, etc. and also from their secondary product such as gum, resins, and latex [4]. Many countries in the world, that is, two-third of the world’s population depends on herbal medicine for primary health care. The reasons for this is because of their better cultural acceptability, better compatibility and adaptability with the human body and pose lesser side effects [5].

Catharanthus roseus is an evergreen ever blooming herb which has its origin in central Madagascar Island. Periwinkle is recorded for as back as 50 B.C. in folk medicine literature of Europe as diuretic, hemorrhagic and wound healing. It was introduced to many parts of the world in 18th century. It is believed to be brought in India by the Portuguese mercenaries in the middle of 18th century in Goa. Presently it is cultivated in Europe, India, China, and America [6]. The plant has spread all over tropical and subtropical parts of India and grows wild all over the plains and lower foothills in Northern and Southern hills of India. In Malaysia it is locally called as Kemunting Cina. The periwinkle logo as a symbol for hope for cancer patients is used by National Cancer Council of Malaysia [7]. The name Catharanthus L.G. Don is derived from the latin words Katharos (pure) and anthos (flower), referring to the neatness and beauty of the flower. Reichenbach, in 1935, first recognized and generically separated the existing genus Catharanthus from Vinca and designated it as Lochnera. George Don, in 1935 assigned it the name Catharanthus L.G.Don [7].The name catharanthus comes from the Greek for "pure flower" and roseus means red, rose, rosy. It rejoices in sun or rain, or the seaside, in good or indifferent soil and often grows wild. It is known as 'Sadabahar' meaning 'always in bloom' and is used for worship [8].This plant is a terpenoid indole alkaloids producing plant [9]. The plant is an important source of indole alkaloids, which are present in all plant parts. The leaves and stems of the plants are the source of dimeric alkaloids, vincristine and vinblastine that are indispensable cancer drugs, while roots have antihypertensive, ajmalicine and serpentine [10]. Vincristine and vinblastine alkaloids are used in the treatment of various types of lymphoma and leukemia [11]. All parts of the C. roseus are used for different medical purposes.

Scientific Classification

Botanical Name(s): Vinca Rosea (Catharanthus roseus) Family Name: Apocynacea Kingdom: Plantae Division: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants) Class: Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons) Order: Gentianales Family: Apocynaceae Genus: Catharanthus Species: C.roseus[12].Vernacular Names

Catharanthus roseus has acquired a variety of vernacular names during its expansion and naturalization over the tropics and subtropics, as listed below in the Table 1 [13] Table 1: Vernacular Names of Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) in Different Countries| Country | Common Name |

|---|---|

| India | Sadaphul, Ushamanjairi, Ainskati, Billaganneru, Nayantara, Nityakalyani, Periwinkle, Rattanjot, Sadabahar |

| Philippines | Atay-biya, Chichirica, Kantotan, Tsitsirika |

| Brazil | Boa-noite |

| West Indies | Brown man’s fancy, Old maid, Pink flower, Ram goat Rose, Red rose, Sailor’s flower |

| Dominica | Caca poule |

| Guatemala | Chatilla |

| Peru | Chavelita |

| Vietnam | Dua can |

| Venda | Liluvha |

| Madagascar | Madagascar periwinkle |

| Kenya | Maua |

| Sri Lanka | Mini-mal, Patti-poo |

| Bangladesh | Nyantra |

| Japan | Nichinich-so |

| Mexico | Ninfa |

| Guyana | Periwinkle |

| Jamaica | Periwinkle |

| USA | Periwinkle |

| French Guiana | Pervenchede |

| Thailand | Phaeng phoi farang |

| Pakistan | Sada-bahar |

| Rodrigues Islands | Saponaire |

| Cook Islands | Tiare-tupapaku-kimo |

| Europe | Vinca branca |

| Spain | Vinca rosada |

Botanical Description of C. Roseus

It is an herbaceous plant or an evergreen subshrub growing to 32 in 80 cm high. It has glistening, dark green, and flowers all summer long. The flowers of the naturally appear pale pink with a purple “eye” in their centres. Erect or accumbent suffrutex, to 1m, usually with white latex. Stems is green, often permeate with purple or red. Leaves: Oval leaves (1-2 in long) decussate, petiolate; lamina variable, elliptic, obovate or narrowly obviate; apex mucronate. Flowers: 4-5 cm, classy, white or pink, with a purple, red, pale yellow or white center. Follicle 1.2-3.8 × 0.2-0.3 cm, susceptible on the axial side. Seeds 1-2 mm, are numerous and grooved on one side.Climate, Soil and Propagation

Flowering Period: Throughout the year in equatorial conditions, and from spring to late autumn, in warm temperate climates.

Soil: Full sun and well-drained soil is preferred. Light: Bright light included three or four hours of direct sunlight daily, is essential for good flowering. Temperature: Normal room temperatures are suitable at all times. It cannot tolerate temperatures less than 10ºC (50ºF).Watering: Water the potting mixture plentifully, but do not allow the pot to stand in water.

Feeding: As the flowering begins, apply standard liquid fertilizer every two weeks. Plants are not tolerant of excessive fertilizer. Irrigation: They need regular moisture, but avoid overhead watering. It should be watered tolerably during the growing season, but it is relatively drought resistant once entrenched. They will regain after a good watering. Fertilizing: The plant is not heavy breeders. If necessary, feed biweekly or once monthly with a fair amount liquid fertilizer. Too much fertilizing will produce abundant foliage instead of more Blooms [14, 15, 16].Geographical Distribution

Catharanthus roseus is native to the Indian Ocean Island of Madagascar. In many tropical and subtropical regions worldwide it has been introduced as a popular ornamental plant. It commercially cultivated in Spain, United States, China, Africa, Australia, India, and Southern Europe for its medicinal uses. The drugs derived from this plant find major markets in USA, Hungary, West Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, and UK [17,18]. It is now common in many tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, including the Southern United states.Traditional Medicinal Use of Catharanthus roseus

In traditional medicine, C. Roseus has been used to treat a variety of aliments in different parts of the word where the plant has naturalized. Folk remedies and traditional uses of Catharanthus roseus are summarized in the Table 2. Table 2: Traditional Medicinal Use of Catharanthus roseus| Country | Used as |

|---|---|

| Australia | Hot water extract of dried leaves is taken orally for menorrhagia, diabetes and extract of root bark is taken orally as febrifuge [19,20]. |

| Brazil | The hot water extract of dried entire plant is taken orally by human for diabetes mellitus [21, 22]. |

| China | Hot water extract of the aerial parts is taken orally as a menstrual regulator [23,24]. |

| Cook Island | Decoction of dried leaves used orally to treat diabetes, hypertension and Cancer [25]. |

| Dominica | Hot water extract of leaves is taken orally by pregnant woman to combat primary inertia in childbirth and the boiled leaves are drink to treat diabetes [26]. |

| England | Hot water extract of dried entire plant is taken orally for the curing of diabetes [27]. |

| Europe | Decoction of dried leaves is taken orally for diabetes mellitus [28]. |

| France | Hot water extract of entire plant is taken as an antigalactagogue [23]. |

| French Guina | Hot water extract of entire plant is taken orally as a cholagogue [29]. |

| India | The hot water extract of dried entire plant is taken orally by human for cancer. Hot water extract of dried leaves is taken orally to Hodgkin’s disease. The root extract is taken orally for menorrhagia [24, 30]. |

| Jamaica | Hot water extract of dried leaves is taken orally for diabetes [31]. |

| Kenya | Hot water extract of dried leaves is taken orally for diabetes [31]. |

| Mexico | Infusion of whole plant is taken orally for stomach problem [32]. |

| Mozambique | Hot water extract of leaves is taken orally for diabetes and rheumatism and the root extract is taken orally as hypotensive and febrifuge [33]. |

| North Vietnam | Hot water extract of the aerial parts is taken orally as a menstrual regulator [23, 24]. |

| Pakistan | Hot water extract of dried ovules is taken orally for diabetes [34]. |

| Peru | Hot water extract of dried entire plant is taken orally by human adults for cancers, heart disease and leishmaniasis [35]. |

| Philippines | Hot water extract of root is taken orally by pregnant women to produce abortion [24, 36, 37]. |

| South Africa | Hot water extract of dried leaves is taken orally for menorrhagia and diabetes [19] |

| South Vietnam | Hot water extract of the entire plant is taken orally by human adults as an antigalactagogue [23, 24]. |

| Taiwan | Decoction of dried entire plant is used orally by human adults to treat diabetes mellitus [37] and liver disease [38]. |

| Thailand | Hot water extract of dried entire plant is taken orally for diabetes [39]. |

| USA | Hot water extract of leaves are smoked as a euphoriant [40]. |

| Venda | Water extract of dried root is taken orally for venereal disease [41]. |

| Vietnam | Hot water extract of dried aerial parts is taken orally as drug in Vietnamese traditional medicine, listed in Vitnamese pharmacopoeia (1974 Edition) [42]. |

| West Indies | Hot water extract of leafy stems is taken orally for diabetes [43]. |

| Zimbabwe | Hot water extract of crushed roots is taken orally for stomach [44]. |

Modern Use of C. Roseus

Anti-cancer Activity C. Roseus extract is rich in alkaloid and found to contain a wide range of alkaloid possessing anticancer activity including vinblastine, vincristine, vindoline, vindolidine, vindolicine, vindolinine and vindogentianine [45, 46, 47]. C. Roseus extract becomes more and more precious to blood cancer patients [48]. C. Roseus extract like vinblastine and vincristine were the first plant-derived anticancer agents deployed for clinical use as chemotherapy for many different types of cancer such as: lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-hodgkin), testicular cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, sarcoma, etc. [49] Vincristine was found to be produced by Fusarium oxysporum which is an endophyte of this host [50], while another group has isolated the vinblastine from an endophytic fungus [51].Vinblastine sulphate has been utilized for treatment of Hodgkin’s disease, lymphosarcoma, choriocarcinoma, neuroblastoma, carcinoma of breast and lungs and other organs in acute and chronic leukemia. Vincristine sulphate, an oxidized form of vinblastine [52] arrests mitosis in the metaphase and is effective in treating acute leukemia (in children), lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, Wilkin’s tumor, neuroblastoma and reticulum cell sarcoma [11].

Vinblastine and vincristine bind specifically to tubulin-heterodimeric protein common in all eukaryotic cells. Tubulin and its polymer form are microtubules that pay an important role in maintaining cell morphology, intracellular transport and building mitotic spindle during cell division [53]. Alkaloids inhibit the incorporation of tubulin into microtubules, thereby preventing cell division. Therefore, they limit the formation of excess white blood cells in blood cancer patients. The alkaloids possessing, anticancer property is enlisted in Table 3.

Table 3: It shows the alkaloids possessing anticancer property, drug names and its clinical uses| Vinca alkaloid | Related drug | Clinical uses |

| Vincblastine | Velban | Hodgkins disease, testicular germ cell cancer |

| Vincristine | Oncovin [54] | Leukemia, lymphomas |

| Vinorelbine [55] | Navelbine | Solid tumors, lymphomas, lung cancer |

| Vindesine [56] | Eldisine [57] | Acute lymphocytic leukemia |

Anti-diabetic Activity

From the Traditional period itself, C. roseus has been used to cure diabetes and high blood pressure as it was believed to promote the insulin production or to increase the body’s usage of the sugars from the food in case of diabetes [58]. The “periwinkle tea” prepared from leaf decoction of C. roseus is used for curing diabetes [58]. The antidiabetic compounds present in Catharanthus roseus are Vindoline and Vindogentianine. Vindoline is found to increase the insulin level in mouse insulinoma cell line (MIN6). Vindoline at a concentration higher than 50 μM can raise the insulin secretion to the maximum level [59]. According to Alkreathy and Ahmad [60], Catharanthus roseus ethanolic extract combined with the ursolic acid exhibits high levels of insulin production. The combination using equal proportions of Catharanthus roseus ethanolic extract and ursolic acid (25 mg: 25 mg) hiked the insulin production from 5.93 μU/ml to 13.65μU/ml in diabetic rats. This proved the scope of Catharanthus roseus and ursolic acid combination as a feasible alternate therapy [60].Anti-Alzheimer Activity

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system and accounts for 50–60% of dementia in patients [61]. It is characterised by profound memory impairment, emotional disturbance and personality changes in the late stages of life [62]. Cholinergic neurons in the neocortex and hippocampus are suggested to be predominantly affected in AD, resulting in the cholinergic hypothesis, which associates AD symptoms to cholinergic deficiency [63]. The current effective AD therapy is to increase acetylcholine (Ach) levels by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AchE), an enzyme responsible for degrading Ach in the synaptic cleft [61, 63]. Vinpocetine has been reported to have a variety of actions that would hypothetically be beneficial in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [18]. The aqueous extract of C. roseus leaf, stem and root has been shown to effectively inhibit AchE in an in-vitro microassay [64]. Additionally, serpentine, an alkaloid presents in C. roseus leaf, stem and root displayed a strong activity against AchE [65]. These findings revealed that this plant is a potential source of active compounds for the pharmacological management of neurodegenerative conditions including Alzheimer’s disease.Anti-oxidant activity

C. roseus extract including vindoline, vindolidine, vindolicine and vindolinine were found to possess antioxidant properties [45, 66-68] which could reduce and prevent the oxidation of other molecules. The anti-oxidant potential of the ethanolic extract of the roots of the C. roseus was obtained by using different system of assay such as Hydroxyl radical-scavenging activity, uperoxide radical-scavenging activity, DPPH radical- scavenging activity and nitric oxide radical inhibition method [69].Anti-helminthic activity

Helminthes infections are the chronic illness, affecting human beings and cattle. Catharanthus roseus was found to be used from the traditional period as an anti-helminthic agent. The anti-helminthic property of C. roseus has been evaluated by using Pheretima posthuma as an experimental model and with Piperazine citrate as the standard reference [70]. The plant has been reported to possess vermifungal properties. Dried leaves, incorporated into the soil produce nematicidal and ovistatic effects [6].As a cardiovascular drug

The roots of the plant were found to accumulate ajmalicine and serpentine, which are the important components of medicines that are used for controlling the high blood pressure and other types of the cardio-vascular maladies [71, 72].Anti-microbial activity

The anti-bacterial activity of the leaf extract of the plant was checked against microorganism like Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM2036, Salmonella typhimuruim NCIM2501, Staphylococcus aureus NCIM5021 and was found that the extracts could be used as the prophylactic agent in the treatment of many of the disease [73].Anti-ulcer activity

Vincamine and Vindoline alkaloids of the plant showed anti-ulcer property. The alkaloid vincamine, present in the plant leaves shows cerebrovasodilatory and neuroprotective activity. [74]. The plant leaves proved for anti-ulcer activity against experimentally induced gastric damage in rats.Anti-diarrheal property

The anti-diarrheal activity of the plant ethanolic leaf extracts as tested in the wistar rats with castor oil as an experimental diarrhea inducing agent in addition to the pretreatment of the extract. The anti-diarrheal effect of ethanolic extracts C. roseus showed the dose dependant inhibition of the castor oil induced diarrhea [75].Anti-gonorrhea property

Although the literature indicates that C. roseus extracts have been used in the treatment of various diseases such as cancer, stomach ache, urogenital infections and diabetes mellitus, its exclusive use is to treat gonorrhea. Bapedi traditional healers highly utilize it for gonorrhoea might provide a useful lead to the discovery of new affordable and readily available plant-based gonorrhoea treatment [76].Wound healing property

Rats treated with 100 mg /kg/day of the Catharanthus roseus ethanol extract had high rate of wound contraction significantly decreased epithelization period, significant increase in dry weight and hydroxyproline content of the granulation tissue when compared with the controls. Wound contraction together with increased tensile strength and hydroxyproline content support the use of C. roseus in the management of wound healing [77].Anti-atherosclerotic activity

In study, significant anti atherosclerotic activity as suggested by reduction in the serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-c, VLDLc and histology of aorta, liver and kidney with the leaf juice of Catharanthus roseus (Linn.) G. Donn. Could have resulted from the antioxidant effect of flavonoid, and probably, vinpocetine like compound present in leaf juice of Catharanthus roseus (Linn.) G. Donn [78].

Bio-pesticidal property Biological activity of solvent extracts of Catharanthus roseus were evaluated against larvae of gram pod borer Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Ethyl acetate fractions of leaf extract of C. roseus was found to be a potent biopesticide [79]. Insecticidal properties of Catharanthus roseus have also been reported by Deshmukhe [80].Phytoremediation property

Phytoremediation used to remove pollutants from environment components [81]. Observed that the impact of cadmium and lead on Catharanthus roseus. They concluded that during germination the toxic effects of cadmium and lead with respect to C. roseus are the maximum and the plant gradually becomes more resistant to these heavy metals as it attains maturity. The phytoremediation potential of Catharanthus roseus with respect to chromium has been analyzed by Ahmad and Mishra (2014) [82]. C. roseus was shown to absorb up to about 38% of the amount of Cr present in primary and secondary sludge amended soil through roots and accumulate it to about 22% in leaves, thereby, proved useful in the reclamation and remediation of chromium contaminated soil and land. Catharanthus roseus has been used for lead and nickel phytoremediation by Subhashini and Swamy [83].CONCLUSION

The author concluded that Catharanthus Roseus is an important therapeutic herb for alleviating the ailments of human kinds. Catharanthus roseus was investigated from the ancient time for their alkaloids components and their therapeutic effect. The plants have a large number of phytochemical constituents that can be used for a variety of medical purposes. The plant also possesses various properties such as anti-cancerous, anti-diabetic, anti-helminthic, anti-diarrheal, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant, biopesticidal, phytoremediation, etc. Hence, it has a lot of therapeutic potential that needs to be investigated further.

References

- Patharajan S, Balaabirami S. Int J Pharm. 2014, 1(2): p. 138-143.

- Ajaib M, Zaheer-Ud-Din Khan, Khan N, et al., Pak J Bot. 2010, 42(3): p. 1407-1415.

- Haq F, Ahmad H, Alam M. J Med Plants Res. 2011, 5(1): p. 39-48.

- Khan KY, Khan MA, Niamat R, et al., Afr J Pharmacy Pharmacol. 2011, 5(3): p. 317-321.

- Sandberg F, Corrigan D. Natural remedies: their origins and uses. 2001.

- Kaushik S, Tomar RS, Gupta M, et al., Eur J Acad Res. 2017, 5(2): p. 1237-1247.

- https://makna.org.my/periwinkle.asphttp://www.makna.org.my/periwinkle.asp

- Swanberg A, Dai W. Hort Science. 2008, 43(3): p. 832-836.

- Rao AS, Fazil M. Glob j res anal. 2013, 2(7): p. 2277-8160.

- Mu F, Yang L, Wang W, et al., Molecules. 2012, 17(8): p.8742-8752.

- Aslam J, Khan SH, Siddiqui ZH, et al., Pharmacie Globale, 2010, 4(12): p. 1-16.

- Erdogrul ÖT. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2002, 40(4): p. 269-273.

- Nisar A, Soh Mamat A, Hatim Md, et al., IRJPS. 2016, 3(2): p. 631-653.

- Sharma SK. Medicinal Plants used in Ayurveda. 1998, 193: 48.

- Joshi SK, Sharma BD, Bhatia CR, et al., The Wealth of India Raw Materials Series. 1992, 3: 270-271.

- Tandon N, Yadav SS. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 197: p. 39-45.

- Rasoanaivo P. Asian Biotechnol Dev Rev. 2011, 13(3): p. 7-25.

- Łata B. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2007, 6(2): p. 403-411.

- Bhandari PR, Mukerji B. Gauhati Ayurvedic Coll. Mag., 1959, 8: p. 1-4.

- Webb LJ. Guide to medicinal and poisonous plants of Queensland. 1948, p. 232.

- Brandao M, Botelho M, Krettli EAU. Ciência e Cultura. 1985, 37(7): p.1152-1163.

- De Mello JF. J Ethnopharmacol. 1980, 2(1): p. 49-55.

- Farnsworth NR. Lloydia. 1961, 24(3): p. 105-138.

- Virmani OP, Srivastava GN, Singh P. Indian Drugs. 1978, 15: p. 231-252.

- Holdsworth DK. Int J Crude Drug Res. 1990, 28(3): p. 209-218.

- Hodge WH, Taylor D. WEBBIA. 1956, 12(2): p. 513-644.

- WAR Thompson. J Roy Coll Gen Pract. 1976, 26: p. 365-370.

- Swanston-Flatt SK, Day C, Flatt PR, et al., Diabetes Research (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1989, 10(2): p. 69-73.

- Luu C. Plant Med Phytother. 1975, 9: p. 125-135.

- ANON: Probe. 1985, 24(2): p. 234-236.

- Morrison EYSA, West ME. West Indian Med J. 1982, 31: p. 194-7.

- Johns T, Kokwaro JO, Kimanani EK. Economic Botany. 1990, 44(3): p. 369-381.

- Amico A. Fitoterapia. 1977, 48: p. 101-139.

- Atta-Ur-Rahman. Bull Islamic Med. 1982, 2: p. 562-568.

- Ramirez VR, Mostacero LJ, Garcia AE, et al., 1988, 54.

- Zaguirre JC. Guide notes of bed-size preparations of most common local (Philippines) medicinal plants. 1944.

- ANON: Description of the Philippines. Part I., Bureau of Public Printing, Manila, 1903.

- Hsu FL, Cheng JT. Phytother Res. 1992, 6(2): p. 108-111.

- Yang LL, Yen KY, Kiso Y, et al., J Ethnopharmaco. 1987, 19(1): p. 103-110.

- Mueller-Oerlinghausen B, Ngamwathana W, Kanchanapee P. J Med Assoc Thai. 1971, 54(2): p. 105-112.

- Siegel RK. J Amer Med Assoc. 1976, 236(5): p. 473-476.

- Arnold HJ, Gulumian M. J Ethnopharmaco. 1984, 12(1): p. 35-74.

- Nguywen VD. Proc Seminar of the use of Medicinal Plants in Healthcare. Tokyo. 1977, p. 13-17.

- Chigora P, Masocha R, Mutenheri F. J Sustain Dev Afr. 2007, 9: p. 26-43.

- Tiong SH, Looi CY, Arya A, et al., Molecules. 2013, 18(8): p. 9770-9784.

- Tiong SH, Looi CY, Arya A, et al., Fitoterapia. 2015, 102: p. 182-188.

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Ann Appl Biol. 2003, 143(2): p. 127-133.

- Kalaiselvi A, Roopan SM, Madhumitha G, et al., Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2015, 135: p.116-119.

- Tung CY. J Chuxiong Norm Univ. 2002, 6: p. 39-41.

- Guo B, Kunming LH. J Yunnan Univ. 1998, 20: p. 214-215.

- Almagro L, Fernández-Pérez F, Pedreño MA. Molecules. 2015, 20(2): p. 2973-3000.

- Mishra JN, Verma NK. Intern J Res Pharmacy Pharmaceut Sci. 2017, 2(2): p. 20-23.

- Skarin AT, Rosenthal DS, Moloney WC. National Library of Medicine Blood. 1977, 49(5): p. 759-70.

- Sisodiya PS. Int J Res Dev Pharm L Sci. 2013, 2(2): p. 293-308.

- Rout S, Khare N, Beura S, et al., Int J Agric Res. 2015, 1(8).

- Schmelzer GH, Gurib-Fakim A, Arroo R, et al., PROTA. 2008, 11(1): p. 155.

- Singh SN, Vats P, Suri S, et al., J Ethnopharmaco. 2001, 76: p. 269-277.

- Yao X, Chen F, Li P, et al., J Ethnopharmaco. 2013, 150(1): p. 285-297.

- Alkreathy HM, Ahmad A. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020.

- Yoo YK, Park SY. Molecules. 2012, 17: p. 3524–3538.

- Bartolucci C, Perola E, Pilger C, et al., Proteins. 2001, 42: p.182-219.

- Greenblatt HM, Guillou C, Guénard D, et al., J Am Chem Soc. 2004, 126: p. 15405-15411.

- Pereira DM, Ferreres F, Oliveira JMA, et al., Food Chem. 2010, 121: p. 56-61.

- Pereira DM, Ferreres F, Oliveira JMA, et al., Phytomedicine. 2010, 17: p. 646-652.

- Pham HNT, Sako JA, Vuong QV, et al., J Food Process Preserv. 2018, 42(5): p. e13597.

- Pham HNT, Sako JA, Vuong QV, et al., Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018, 16: p. 405-411.

- Pham HNT, Sako JA, Vuong QV, et al., Mol Biol Rep. 2019, 46: p. 3265-3273.

- Alba Bhutkar MA, Bhise SB. Int J Pharm. 2011, 3(3): p. 1551-1556.

- Agarwal S, Jacob S, Chettri N, et al., Int J Pharm Sci Drug Res. 2011, 3(3): p. 211-213.

- Svoboda GH, Blake DA. The Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Catharanthus roseus L. 1975, p. 45-124.

- Norbert Neuss. Indole and Biogenetically Related Alkaloids/Edited by JD Phillipson and MH Zenk.1980.

- Patil PJ, Ghosh JS. British Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2010, 1(1): p. 40-44.

- Nosálová V, Machova J, Babulová A. Arzneimittel-forschung. 1993, 43(9): p. 981-985.

- Rajput MS, Nair V, Chauhan A, et al., Middle East J Sci Res. 2011, 7(5): p. 784-788.

- Semenya SS, Potgieter MJ. J Med Plants Res. 2013, 7(20): p. 1434-1438.

- Nayak BS, Anderson M, Pereira LP. Fitoterapia. 2007, 78(7-8): p. 540-544.

- Patel Y, Vadgama V, Baxi S, et al., Acta Pol Pharm. 2011, 68(6): p. 927-935.

- Ramya S. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2008, 1: p. 140.

- Deshmukhe PV, Hooli AA, Holihosur SN. Recent Research in Science and Technology. 2010, 2(2): p. 1-5.

- Pandey S, Gupta SK, Mukherjee AK. J Environ Biol. 2007, 28(3): p. 655.

- Ahmad NH, Rahim RA, Mat I. Trop Life Sci Res. 2010, 21(2): p. 101.

- Subhashini V, Swamy AVVS. Universal Journal of Environmental Research & Technology, 2013, 3(4): p. 465-472. Indexed at, Google Scholar

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref